The Misconceptions Around Leisure Travel’s Environmental Impact

On our chests the heavy weight of the climate crisis rests. We have begun to analyse our modern lifestyles as the wildfires blaze, with many wondering could they be at fault? One facet of our global lifestyles to have come under intense scrutiny in recent years is air travel. The Swedish ‘flygskam’ (flight shame) movement has had powerful effects on consumer decision making and made many skeptical of flying. But, within the vilification of all aviation, sight of the vital benefits that sustainable leisure travel brings is at risk of being lost. Here’s why you shouldn’t turn your back on international travel just yet.

Let’s talk about carbon

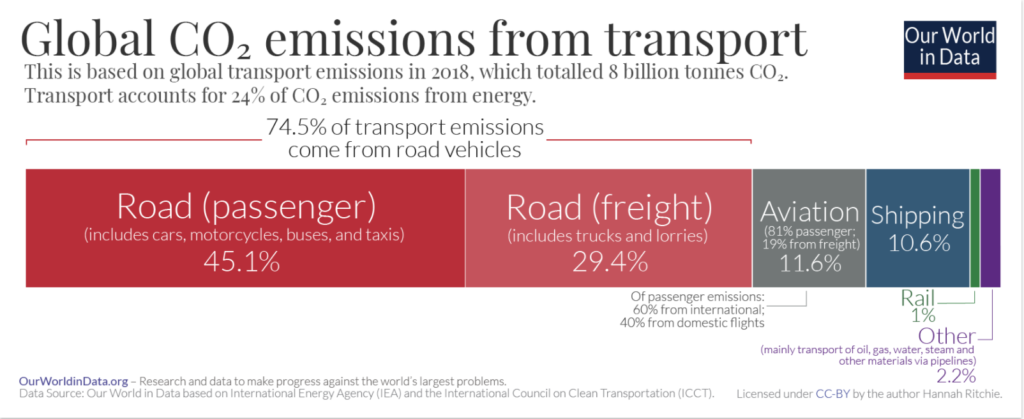

All forms of transport produce 24% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Aviation produces 11% of this, while passenger and freight road transport are responsible for 75%. In the context of all global GHG emissions, air travel (both commercial and cargo) produces between 2-3%. While a seemingly small percentage, aviation forms the largest portion of an individual’s carbon footprint. Looking at it from an individual viewpoint is important too, as this illuminates the vast inequality in CO2 production between a few frequent fliers, and a large portion of the world’s population who don’t fly at all.

In the US, the average person emits 386 kilograms of CO2 per year during domestic flights, compared to just 0.14 kilograms in Rwanda. Yet the picture is muddied further as estimates state that 20% of the US population have never flown in their life, and just over a tenth of the population take 66% of flights. While the “super frequent fliers” of the world undoubtedly need to fly a lot less, there is an argument that suggests flight shaming all travellers is going to do more harm than good.

‘Not every tonne of CO2 is created equal’

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions-from-transport

Research has shown that choosing not to fly can be the environmentally damaging choice for some journeys. To briefly explore this, it all comes down to the variables involved in every trip: distance travelled, energy source, and passenger numbers. For example, trains are far more efficient on short-haul journeys, but this clarity is lost as the distance increases. Efficiency of train travel is also far lower in the US, as they run on diesel fuel, compared to the electric trains across Europe.

A solo long-distance car trip can be more carbon-intensive than some air travel, as occupancy in the car is theoretically at 20%, compared to a full plane of passengers, each sharing the burden of the emissions produced. While this research clouds over the unwavering position of flygskam, at least one thing is made clear: we need to be thoughtful about our travel choices.

As well as assessing our journeys, we need to recognise that flying less for the environment would mean very different things for different people. For example, business travel – synonymous with global jet-setting and airport hotels – is responsible for a great portion of aviation emissions, despite the relatively small number of travellers. Yet the outbreak of COVID-19 has illuminated how adaptable behaviours are, and how superfluous a lot of business air travel is.

In comparison, “the top 20 destinations most reliant on tourism… were only responsible for 0.61% of global passenger aviation emissions in 2018”. A tourist and a business traveller can both be on a return flight to the Maldives, but each of their carbon emissions are not created equally. In the words of Sola Zheng, every tonne of carbon dioxide produced is physically the same, yet “the economic and social aspects of flying require us to further deliberate on reducing aviation emissions”.

In other words, who is likely to have a better impact on the community they arrive in? The tourist staying in independent accommodation, eating at local restaurants and experiencing authentic culture, or the business traveller staying in the chain hotel on a quick turnaround, there for a meeting that could have taken place virtually.

Economic intricacies of travel

Therefore, in being thoughtful about our travel choices, we need to include those we visit too. Evidently, if everyone immediately stopped flying in an effort to help save the environment, an entirely new issue would unfold. Economic collapse would occur the world over, as the GDP of countries heavily dependent on international travel would plummet – COVID-19 providing a glimpse through the window at a world where no one travels at all.

Travel and tourism brings employment to a huge range of sectors, and has been an incredible force of economic growth for developing countries. In Bangladesh 944 jobs are created for every 100 tourists that visit. This has great potential for social mobility, when a “pro-poor tourism” model is employed. To stop flying means a loss of vital income for countless communities around the world.

Without proper infrastructure, choosing not to fly threatens to exacerbate an already high risk of poverty, also shown to be inextricably linked to climate change. As part of the affluent minority of the world’s population, responsible for an overwhelming majority of flights, we must add texture to flight shaming, by assessing our need to travel: how, where, and why.

Caught between environmental and social responsibility, which do you choose?

When it comes to leisure travel, global experiences and sharing cultures, how can one justify air travel? The answer is hidden within three questions:

Why are you travelling?

Where are you travelling too?

How are you travelling, and how often?

In the advent of COVID-19, with ever greater awareness of environmental degradation, people have found a need to justify their flights. Not so justifiable anymore is the world of business travel. Business travellers make up 12% of passengers, but provide airlines with at least 24% of their revenue, up to 75% on some routes. Additionally, business and first class seats are five times more polluting than economy class, as the larger seats mean fewer passengers can fly per kilogram of CO2.

As the widespread use of video conferencing has been normalised, the unquestioned necessity of this form of travel has been rightfully opposed. But as an undeniable pillar of our globalised society, can some air travel be justified?

Why are you travelling?

One can argue many reasons for air travel are morally justifiable. First of all, it seems greatly unfair to demand people quit flying when a globalised world and life has long been promoted. As well as international economies and politics, the world is now full of global families too. Grandparents rooted in a homeland welcome their families from all corners of the earth. Is it fair to tell someone they can’t see or care for their family if they can’t afford a more carbon-efficient transport alternative?

Secondly, the wider availability of flying over the last 70 years has increased many people’s access to cultures other than their own. As the pressure of the climate crisis raises tempers and strains relations, it is more important than ever to be able to connect with those different to yourself.