Can Ethical Climbing Reach New Heights with Indigenous Communities?

I follow on the tail end of a generation of climbers who entered the world of climbing through their dads. My dad is an experienced climber and mountaineer who ensured from the outset that I was educated on the important issues within climbing. Primarily these are the safety practices of the sport, but also of the values of climbing – a love of the outdoors and a reverence for nature.

In today’s climbing world the internet has bought a wealth of knowledge and great resources. But knowledge within the community used to be passed down across generations by word of mouth within tight-knit communities. In this age of mass information, some fundamental questions arise.

What is the due process in the development of ethical climbing?

I hope that my attempt to answer this is merely a beginning in the process of the rise of ethical climbing. As a UK based climber, I have discovered that crag access here is usually determined by land ownership – and once consent is granted for climbers to use a piece of land, the access challenges are significantly reduced. Beyond the preservation of the crag for climbing, there aren’t too many concerns about the significance of our rock.

For this reason, it is worthwhile to turn our attention to the USA, where the sport of climbing meets indigenous pastoralism. The indigenous American peoples, across their 574 recognised nations, have a set of deeply pastoral cultures and traditions dating back thousands of years. With the recent arrival of climbers on the landscapes which indigenous people have nurtured and revered for millennia, ethical questions are raised.

Infringement of Indigenous Lands

Since the occupation of their ancestral lands first began, indigenous Americans have been pushed back further and further into reservations, which are still being threatened today as corporate interests are given priority. Projects such as the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), which has violated the 1851 Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, have been imposed on indigenous land. Indigenous activists have long recognised that treaties regarding their ownership of sacred lands are often held in contempt by the state, and do not withstand opposition to corporate interests.

As of 2021, studies have shown that one in ten indigenous people do not have access to clean drinking water, often as a direct result of pipelines such as the DAPL. Pollution and contamination threaten waterways which have supported indigenous people for millennia. The escalation of this crisis has evolved from cultural violation to the destruction of natural infrastructure which has been cultivated to support native people. At stake is fundamental access to basic sanitation.

“The fact that some climbers have held Native American wishes in contempt is a sad reality, but one that must be confronted.”

I mention this in an article about climbing development as it is important to recognise that issues of climbing development do not exist in a vacuum. This entails not just protecting the rock, but also those communities who have subsisted for thousands of years where your sport has taken an interest in the last fifty.

As an ecotourism writer, I have witnessed the emergence of an ethos of supporting the communities who belong to areas of tourist interest, however, it is not adopted universally. Equally, in the climbing community, I have seen these ideas both being advocated for, and also disregarded.

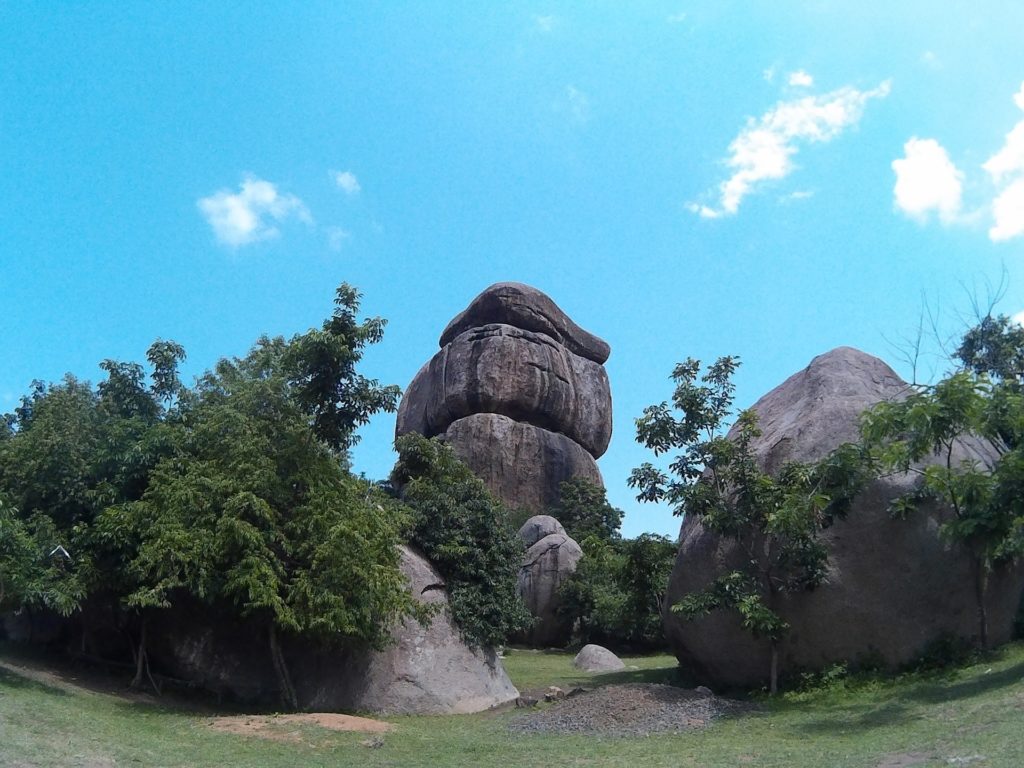

Devil’s Tower, Wyoming

One such point of shared interest between Native Americans and climbers is Devil’s Tower, Wyoming, which is culturally significant to over 20 indigenous nations. A 2018 article from Outside magazine reports how “an increasing number of climbers are choosing to ignore a voluntary June climbing ban that’s been in place for more than 20 years to allow local tribes to hold ceremonies at the site”, stating that “roughly 373 climbers scaled Devils Tower in June 2017, compared to 167 in 1995”.

It is not for me to speculate whether these ascents went ahead due to ignorance surrounding the voluntary June ban, or whether the ban has been recognised and disregarded in favour of an iconic ascent, however, I will note that between the 1990s and the present day, climbing has garnered a significant following online.